Eric Simonson on Writing the Lombardi Playbook

About the author:

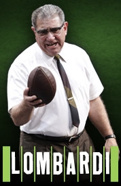

When it comes to writing a play about famed Green Bay Packers football coach Vince Lombardi, the third time’s the charm for Eric Simonson. Lombardi, which opens October 21 at Circle in the Square Theatre, marks the third time the Tony-nominated Wisconsin native has taken a crack at the man whose team won the first two Super Bowls, and the new play is charging toward the Broadway end zone with TV favorites Dan Lauria and Judith Light in tow. Simonson, a Tony nominee for directing The Song of Jacob Zulu in 1993, director of the Oscar-winning documentary A Note of Triumph and author of plays such as Honest and Fake, shared his thoughts about the real Vince Lombardi's inspiring nature and why the coach's story deserves to reach past the confines of Lambeau Field.

![]()

In Wisconsin, where I grew up, it’s hard to get away from the “Lombardi mystique.” It’s in the ether there. I wasn’t old enough to watch Vince Lombardi coach, but I certainly knew his story, which was the Green Bay Packers' story, and I knew his sayings, which were plastered on locker-room and boardroom walls all over the state. When David Maraniss’ biography, When Pride Still Mattered, was published, I didn’t just read it, I devoured it. The book was a revelation—the first intelligent, thoughtful, and thorough biography of a man who, up until that point, had been presented to the public in two-dimensions.

That was 1999. About the same time, I was working on a play about Frank Lloyd Wright called Work Song, which I directed and co-wrote with Jeffrey Hatcher. It premiered at the Milwaukee Repertory Theatre and was successful enough to get subsequent productions at theaters across the country. The experience was a good one and I began to think about the next bio-drama. Since Milwaukee Rep had supported the first one, I thought, “Why not attempt another Wisconsin icon?”

My first pitch to Joe Hanreddy, MRT’s then artistic director, was a play I called Lombardi in Hell, an idea loosely modeled after George Bernard Shaw’s third act of Man and Superman. The prospective play had Vince Lombardi dreaming he had been transported to a sort of limbo where he would argue the value of winning at all costs. The cast of characters included St. Ignatius (Lombardi was schooled by Jesuits), iconic football coach Earl “Red” Blaik, John F. Kennedy and Lombardi’s father, Harry. In the pitch, I described the play as a flight of fancy that might offer something for both the football fan and the subscription audience member. Hanreddy liked the idea, but never acted on it.

Cut to five years later: I’m on the phone with my friend and colleague Jeff Hatcher. We’re talking about this and that, and he tells me that the artistic director of Madison Rep, Rick Corley, had called him about a project—the theater was talking with David Maraniss about creating a play based on his Lombardi book, and they were looking for a writer. Jeff, known for writing the films The Duchess and Casanova, said he had told Corley that if he could see his way to football players dressed in 18th century garb, he might consider it. Otherwise he didn’t think he was right for the job. I begged Jeff to call Rick immediately and recommend me for the job, which he did. It took a little while to get a response, but Rick Corley eventually called me, and we started a conversation, which turned into a commission to write a play—one not too far from my original Lombardi in Hell idea.

That play, which Madison Rep produced a year later, in 2007, was titled The Only Thing. It was a great experience and deserves an account all its own. Suffice it to say, I learned a lot about writing the role of Vince Lombardi. More importantly, I made a very good friend in David Maraniss, who also became one of my favorite collaborators.

When Lombardi producers Fran Kirmser and Tony Pointer approached me, at David’s urging, about writing a new and different kind of play for Broadway, I didn’t hesitate in telling them my interest in Vince Lombardi could fuel five plays. The man is a complex prism of attributes, desires, contradictions and flaws. I also thought, “What a great idea,” to put the story of Lombardi right smack dab in the middle of America’s entertainment crosshairs. The man is an American icon, a hero, perhaps a tragic hero—a tragic American hero. His story is our story and deserves to be told; to be heard, by everyone.

I’ve always been interested in bringing theater to a cross-section of the public—and what better subject than a man who transcended age, time, race and class? My second full Lombardi play is a more story-driven rendering—less fractured and metaphysical, more chronological and dramatic. Not coincidentally, the play focuses not only on Lombardi the coach, but also Lombardi the family man. This was an effort to get to his human side, and show the blemishes in a man most people associate with perfection.

The play also allows me the pleasure of letting my artistic side and my sports-loving side mingle and cross-pollinate. It’s a unique opportunity, and I don’t take it for granted. Last, but not least, I get to export a little Wisconsin heritage. Lombardi and the people who worship him are my people, and this play has been, in a big way, my thank-you card to the state that reared me.

Go Packers.